The time in Brooklyn is now:

Tue Apr 22 07:11:13 2025

We endorse the greatest

health and beauty products

and shampoo on the

market -

Maple Holistics

continue below

The National Gallery

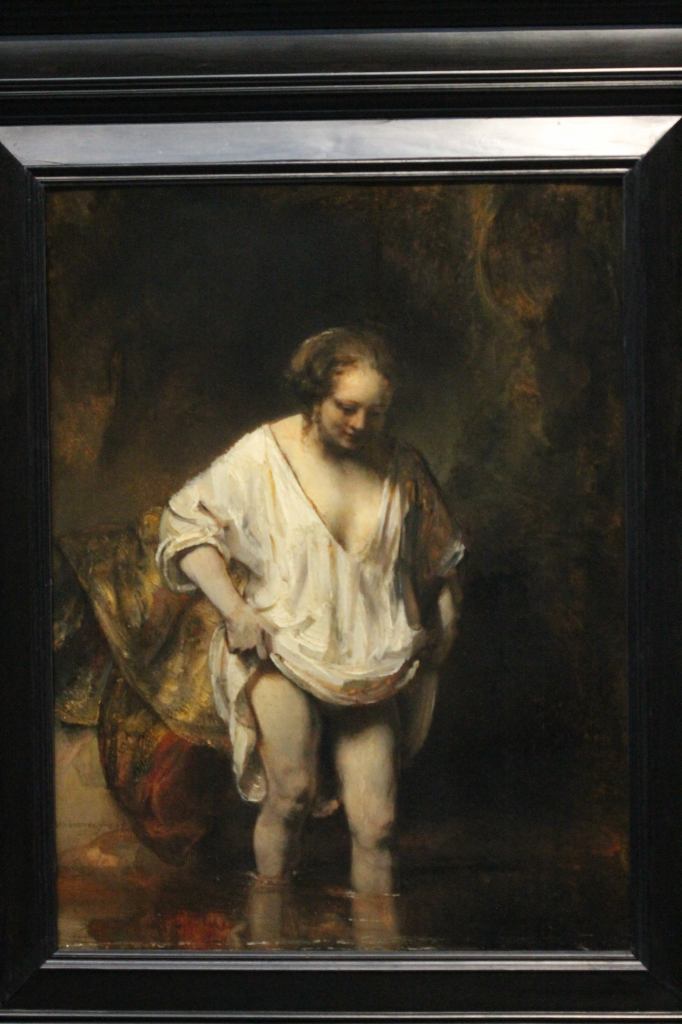

Dutch Masters at The National Gallery

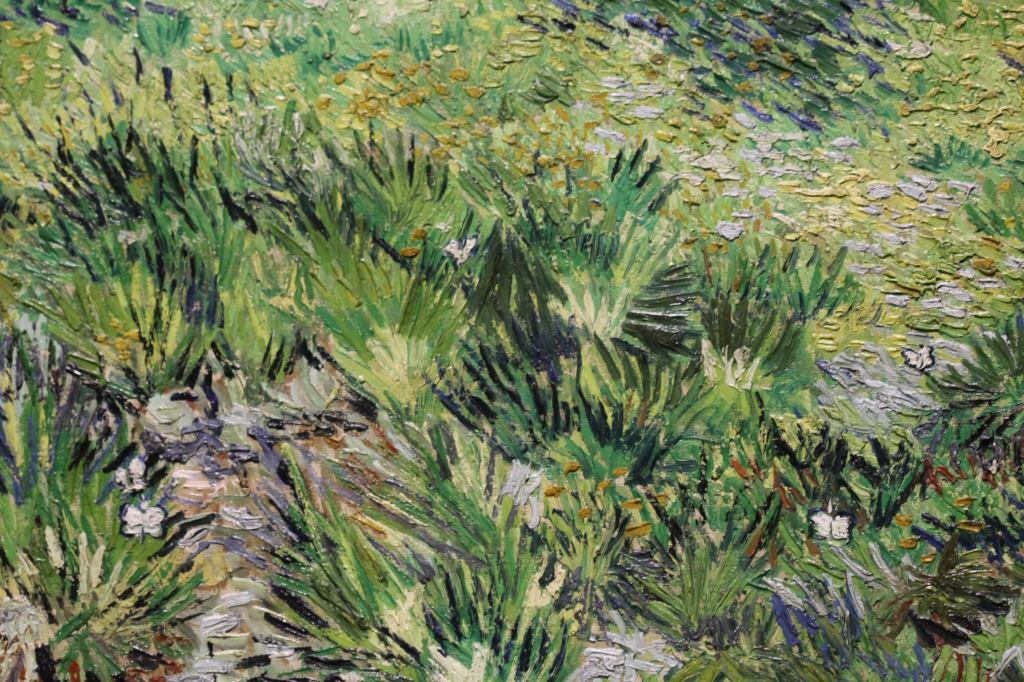

Van Gogh at The National Gallery

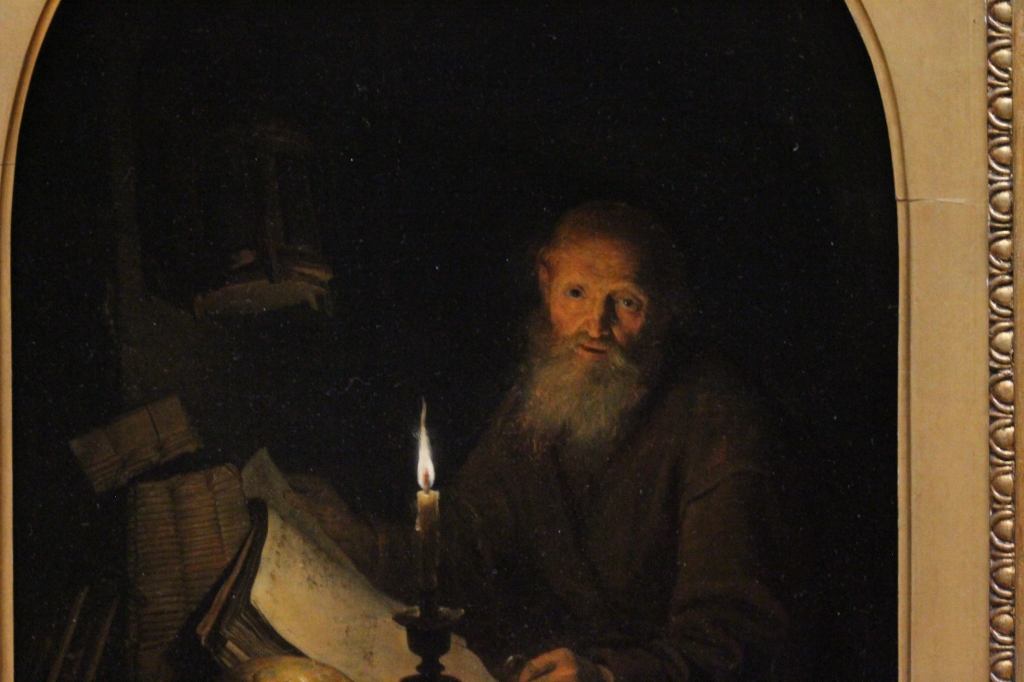

The Wallace Collection at Manchester Square

Jan Steen at The Wallace Collection at Manchester Square

The Dulwich Picture Gallery

Section 2

Section 3

London's place as a touchstone for world culture grows from Britian's central position as the chief colonial power in the world for nearly 300 years. Its empire grew from The Renaissance and Elizabethan England, until the heroic defense of Democracy in World War II. And then it released all of it's colonies under the new internation order after the war.

Britian's cultural development in the arts really picked up when the Dutch Monarchy, the House of Orange, settled into London after decades of religious and civil chaos. Following Henry VIII's break with the Catholic Church, through the 17th Century the Protestants and Catholics presented a multifaceted political power struggle for the political and religious heart and soul of the nation. While this put the British on a distinct path, different from the Catholic Monarchies on the continent, it also lead to civil discontent and civil war. Strangely enough, much of this conflict was largely settled with the friendly conquest of the Dutch Monarchy which was solidly Protestant and was invited to the country by protestant forces within the countries political order. Chaffing under the limitations of the Dutch Republicanism in the Netherlands, the House of Orange found safe harbor on the shores of the British Isles. And while the House of Orange defeated their Republican foes at home, effectively taking control of the Netherland, at the time perhaps the most powerful nation in Europe, the movement to the British crown satisfied many people on both sides of the North Sea. The takeover was the tempered experience and the expections of future English Monachs worked within the experience of stife that the house of Orange had learned from its experience of ruling within the context of the Dutch Republican government. Over time, this might have best served the new Monarchy and preserved it.``

By 1689, the Glorious Revolution was all but over and William and Mary were well established as Monarchs. They brought with them from Amsterdam many advisors, soldiers and artists, a broad swath of Dutch Culture. The merger of the two cultures transformed much of English society and fattened its museums. London rivals Amsterdam as a source for Dutch Art and the Dutch influence kicked off British creativity with the likes of Richard Wilson, Richard Wright, Joshua Reynolds, George Stubbs, Thomas Gainsborough, and J. M. W. Turner all were heavily influenced by Dutch Art.

Meanwhile, in the 18th Century, the British had begun to stack Dutch Art, not to mention many artifacts from antiquity. British were acquiring items from whereever their colonial armies roamed over the protests of natives. In London one can see in short time works from Leonardo to the Parthenon Freeze, to the fossils of Archaeopteryx, in just a few days. It is my Belief that London houses the worlds greatest collections of painting. The Wallace alone is a world class gem.

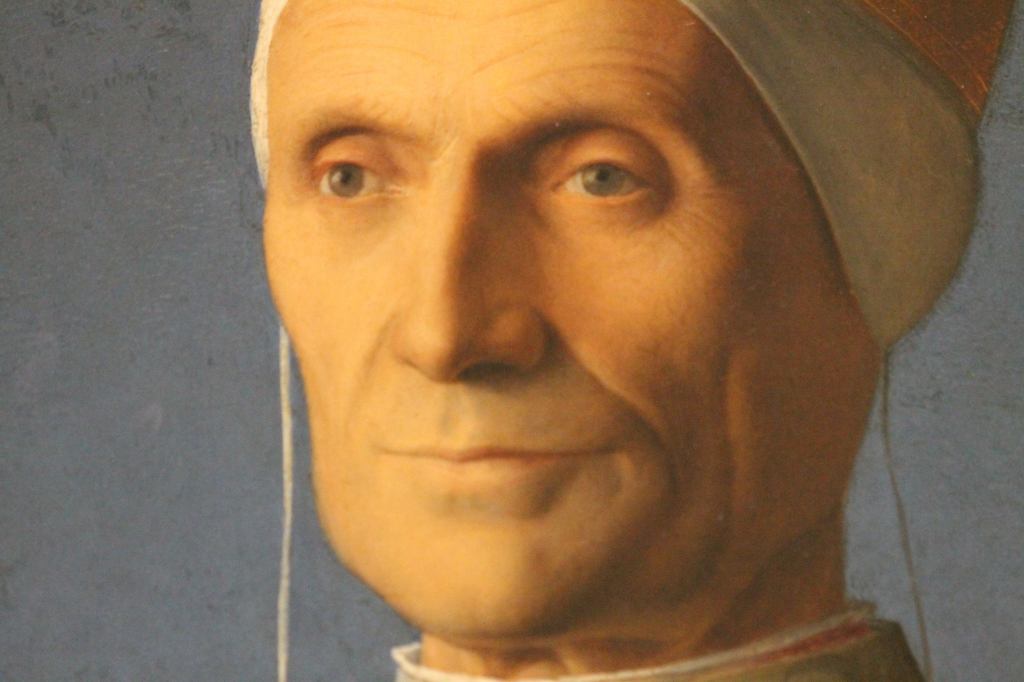

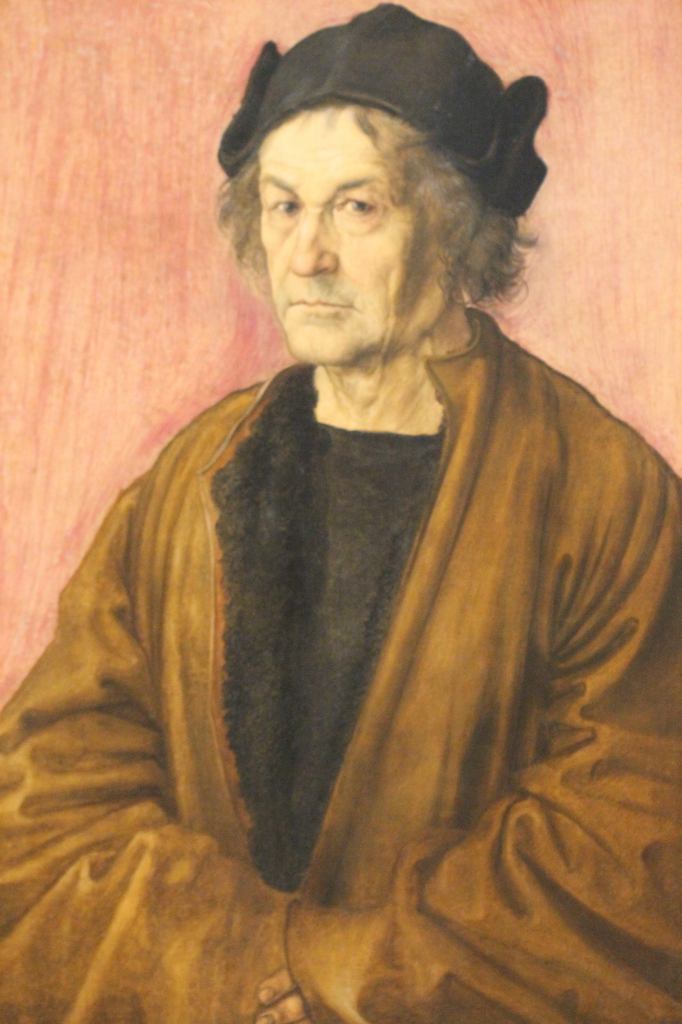

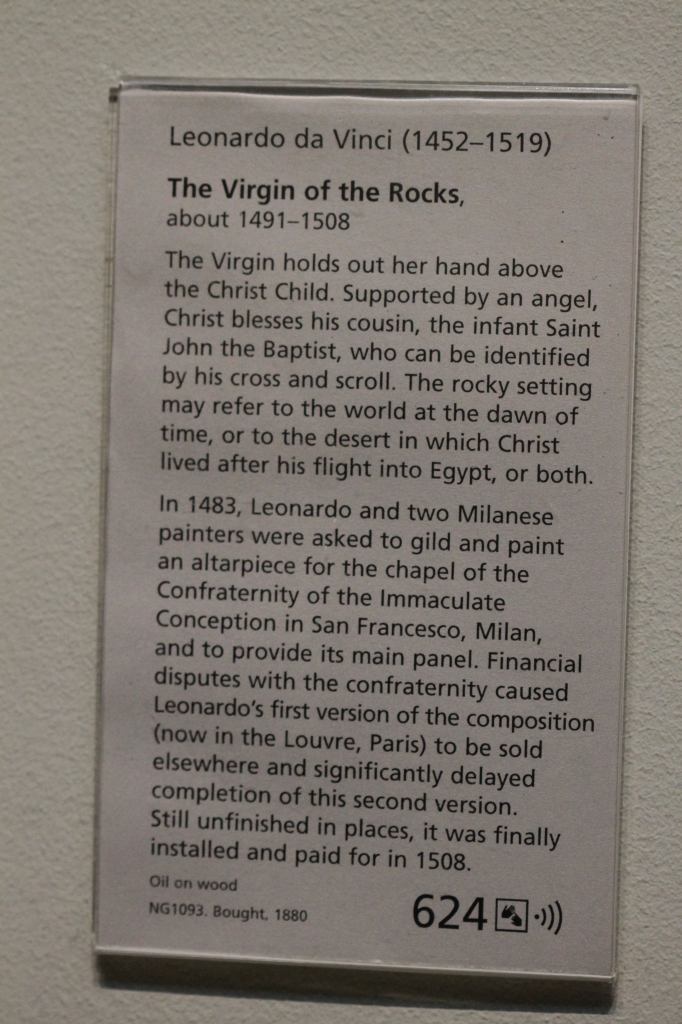

Western Art from before the 16th Century is a major strength of the National Gallery in London. High quality works of this period is rare in North America, and there is poor selection of artists such as Campin, van Eyck, van der Weyden, Veneziano, Dirk Bouts, Bartolomé Bermejo, Gentile Bellini, Sandro Botticelli, Hans Memling, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Raphael, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Quinten Massys, Titan, Bronzino, Jan Brueghel the Elder, and El Greco even at the Metropolitian in New York. Works which I thought would have limited, aesthetic appeal, at least to me, end up being quite impressive in person. Although I had seen collections of works from this period before, to me it blurs into an endless amount of Christian iconography which holds no interest by me at all. The works in London, however, stand on their own as art pieces, and there are far less altarpieces than what I had seen elsewhere.

While much of these works are tempera with lots of gold leaf, and often frescos. oil painting was slowing developing through out this period. Some of the best known and earliest oil paintings are in this gallery. In America, any work of art from the 16th century or before is surprisingly old. In the National Gallery, they are common.

One of the draws that made me come to London was the large number of famous Dutch works I wanted to see. In the end, the museum viewing exhausted me, and there were still places I had wanted to see, which I couldn't get to. Of particular interest to me was to see the only example of a Dutch Peep Show, a three dimension illusion painted in a box which was a Dutch specialty as the artists showed off their expertise in the manipulation of perspective. They are amazingly modern inventions for the 1600's and very few survive. The London Gallery has one of the few intact examples, if not the only one, with the work created by Samuel van Hoogstraten. I saw it. It was amazing. It is impossible to photograph. It is fairly documented on the museum's website.

These peep shows first came to my attention when researching the surviving works of Carel Fabritius. Carel is a painter from Delft who was killed young by a massive explosion that leveled the entire city. Although accepted as an artist second only to Rembrandt (maybe), his most famous surviving work is in the Mauritshuis, the Gold Finch.. It might be that only 13 words survive today, as most were destroyed in the explosion. Two are in the Nation Gallery including a self portrait, which was frustratingly not on display, and a work called "A View of Delft" which seems to have been intended for a peep show.

In addition to that, the museum has perhaps the best collection of Rembrandt's in the world, depending on your individual tastes. It is a near textbook of great works of Rembrandt, with more than a could of Vemeer's, and other masters. This collection would be enough to form a quality museum, and yet it is a small part of the Nation gallery.

To understand the greatness of Vincent, understand that the National Gallery has nearly every great artists in history from DaVinci to Picasso, and yet the busiest exhibit remains the few works by Vincent. This was the only room in the museum that had crowd control.

The Wallace Collection was on the top of my list of Museums to see prior to going to London. I'd known that a dozen or more works of art from the Wallace had been listed in my studies on the Dutch Golden Age. What happened to me when I got there, however, was somewhat unexpected.

First of all, finding the Wallace Collection and Manchester Square was not easy, even with a map. First of all, finding the Wallace Collection and Manchester Square was not easy, even with a map. I was standing with a map on Oxford Street, three blocks from Manchester Square and the museum, and when I asked local folks where Manchester Square was, nobody heard of it. And when I asked where the Wallace Collection was, they thought they may have heard of it, but wasn't sure were it was. That was positively discouraging and I learned that in London, locals aren't that helpful. I finally found a barbershop and asked them where Manchester Street or Manchester Square was. They looked it up on their cellphones and were delighted to discover that Manchester Square was right behind them, go to the end of the block and make a left.

Once I found the townhouse that houses the museum, I found that it wasn't open. It is tucked into a square with a

private park, not much different than Gramacy Park in Chelsea,

Manhattan. The park wasn't open but I was able to take a few pictures

of the square, including some interesting tree bark and vegetation.

The Wallace Collection is a national museum which displays the wonderful works of art collected in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by the first four Marquesses of Hertford and Sir Richard Wallace, the son of the 4th Marquess. It was bequeathed to the British nation by Sir Richard's widow, Lady Wallace, in 1897.Say what? What are they talking about? They probably have the third largest collection of Dutch Golden Age Art, which is the single largest burst of art production by a single cultural period. For 70 years the Dutch were crazy about art, and the rest of Europe was amazed that even the baker and the fish monger likely had great works of art hanging in their homes and work places. The Dutch were touched by God. And they think this collection as being a backdrop to there Rocco and Armour collections. They are totally lost, and so was I went I entered. I finally went upstairs to see the masters, and to my dismay, mostly they have these paintings stacked 3 or 4 high, in straight lines across the walls. You can see visible dust on much of the works of art. They were too high to dust, let alone view. But when I got done with my tour of the museum, I was extremely pleased at seeing so many great works that I had read about, and then I was surprised to see what is likely the greatest painting in created.

The artists on display is a who's who of Dutch Art society from the 1600's. They have 6 verifiable Rembrandt's, and maybe more. They also has some of the finest works of Hals, Jan Steen (five paintings), Willem van de Velde the Younger (eight paintings), Aelbert Cuyp (Six paintings), Caspar Netscher (five paintings), Gabriel Metsu (five paintings), Gerard ter Borch, Ferdinand Bol, Anthony van Dyck (five paintings),Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Meindert Hobbema (at least two paintings), Melchior d'Hondecoeter (three paintings), Pieter de Hooch (two paintings), Karel du Jardin, Jacob Jordaens, Nicolas Maes (three paintings), Aert van der Neer (three painting), Adriaen van Ostade, Isack van Ostade, Nicolas Poussin, Jacob van Ruisdael (five paintings), David Teniers the Younger (two paintings), Adriaen van de Velde, Jan Weenix, among others. The more you know about Dutch art, the more you come to love this Museum.

When you go upstairs, you eventually get to this hall, you hit the jackpot. After walking through some of the museum, this room took me by surprise and the painting to the immediate right left me mesmerized for more than 2 hours.

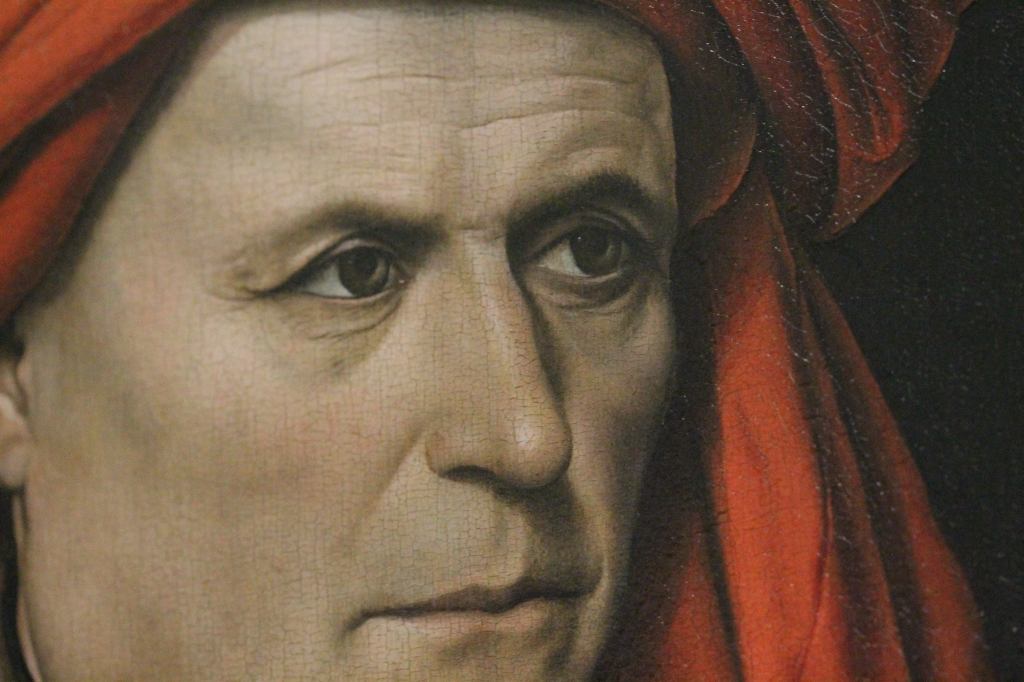

We have all seen images of the Laughing Cavalier, so we smugly feel familiar with it. You might think, hey it's a nice painting, even a fun painting, but what would make this work the greatest painting ever? Why put it above the Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, or above the Mona Lisa, or rank it higher than Vemeer's Allegory of History or give it greater praise than Michelangelo's the Sistine Chapel? What puts this painting ahead of the pack is that is has a sublime mixture of photographic realism (centuries before the camera), with a hidden surrealism in the brush strokes, and the formation of the image. No painting has ever been done quite like this, although it has been attempted. Within this painting exists the essence of abstract expressionism, such that, when you examine this painting closely, it is hard to understand that the painting forms a coherent image when you stand back. If realistic painting is itself an illusion of three dimensional space on a two dimensional plane, this painting is the ultimate illusion, because if one looks at the rhythm and structure of the brush strokes, that brush work seemingly have nothing to do with the use of color and shape needed to mold a complete image. And yet, there it is. This is more than an optical illusion. This is a master craftsman, Franz Hals, who understands the relationship of every near microscopic brush stoke to a complete image, and who can therefor play with those brush strokes to produce an work of art within a work of Art.

In addition to the abstract layer to the brush strokes, the combination of two two methodologies to the painting adds to the effect of focusing the viewer on the face of the Cavalier. A traditional smooth technique is used in the face, and the rough technique applied increasingly as you move away from the eyes. This intensifies the viewers focus on the broad comical face, which when examined closely, gives way to an air of seriousness, even danger. This is a potentially dangerous individual, a lion resting in the grass. This is a portrait of a young man of great pride, and who shows a transient emotion to a more serious expression, even a bit discontented. While the painting is called the Laughing Cavalier, a close look at the person in the painting proves that he is not only not laughing, but he is even a bit cross. This adds to the subterfuge of the image. While the expression is relaxed and calm, it is hardly trivial.

This level of smoothness of the brush stroke transform as one moves out from the focus of the painting, breaking into more abstraction in ones peripheral vision.

Another level of greatness to this painting is that the painting projects into the personal space of the viewer, and insists that you have to view the painting from the right, and not the left. I stood in front of this painting for an hour and watched viewer after viewer correct there position from in front of the painting, to standing to the right of the painting. The perspective just doesn't look correctly from the left. One needs to stand to the right to enjoy the painting.

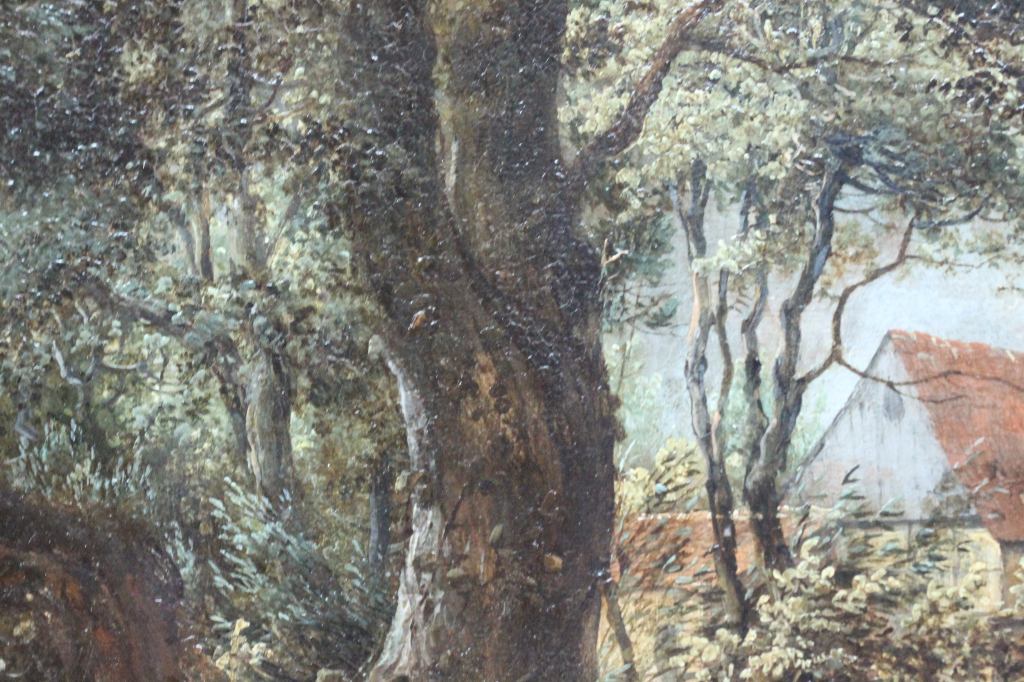

Across the hall from the Laughing Cavalier is one of the nicest Hobbema

landscapes that one will find. This example is a little different from others

prime examples in that it has no waterfall. But the balanced composition and

the trees movement is nearly perfect.

One of the aspects of Hobbema that makes him a superior landscape artist is

that the wind that runs through it paintings is entirely consistent. One can

always trace the flow of the wind through the painting, especially through the

trees. It is not blowing left on one side of the painting and right on the

other part. It always sweeps through the composition as it would in life.

Hobbema solves the problem of imaging trees, and tree leaves, better than any

other artist, past or present.

Next down the hall, about 20 feet up in the air on the right hand wall is this

splendid Rembrandt. In fact, this is one of the great full length portraits by

Rembrandt that I've seen and in any other museum, this work would be displayed at eye

level. At the Wallace, this painting is jacked way up to the heigh ceiling,

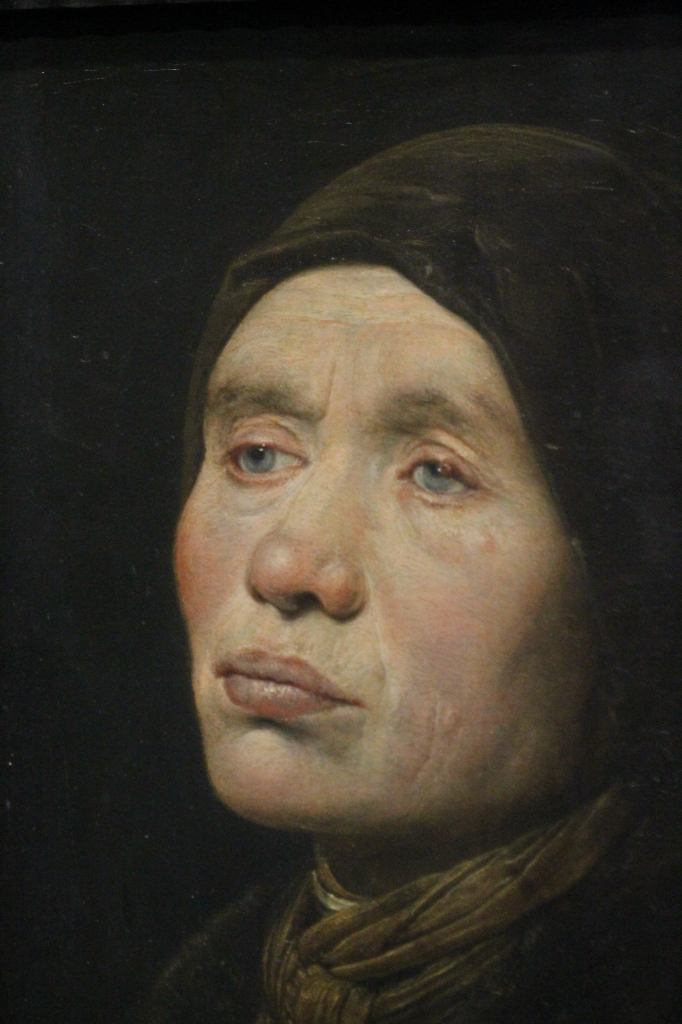

making it very difficult to view. This is a mother and child image, with the

mother handing a coin to her child (to run an errand?). It is a magnificent

rendering, and little known, for what ever reason. It is posible that this

painting is not a Rembrandt. The Rembrandt group has called it into question,

but today it is generally accepted. Regardless, it is a magficicant work.

Susanna van Collen and her Daughter Anna

As we move now through the Wallace Collection, we start to see a startling number of Dutch Masters, stacked along the walls of the townhouse that makes this museum. Photography is often difficult. First, there was so many paintings that one almost felt embarrassed to photograph them all. If you imagined yourself at the about the 1650's in Amsterdam, the great market for paintings was often in taverns and bars. Paintings would be everywhere, and perhaps the shear commonality of superb works would cheapen their value. Under such conditions, I imagine we would often see paintings displayed as they are here and the Wallace, that is difficult to view, often high up on high ceilinged walls, collecting dust. It is an interesting perspective, but it makes it hard to appreciate these masterpieces or to get good pictures. Traveling as much as I had been, one also just gets tired. So please excuse my photography in this section. Often better images are on google arts of the museums main website.

After Hobbema, we find this prized Jacob Ruishdael, with a darkened landscape

and a roaring waterfall. This is a classic Ruisdael theme that we see examples

of at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The best Ruisdael's (Jacob) are

viewable in the Hals Museum in Harlem.

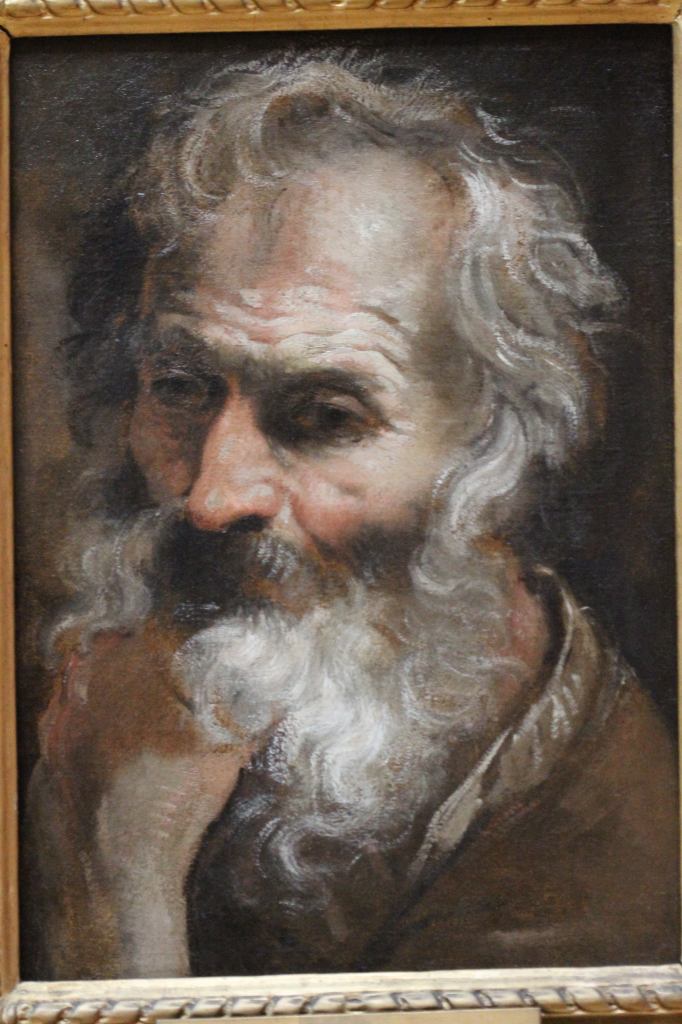

This painting, the Centurion Cornelius, was attributed to Rembrandt and it is

carved into the frame that it is a Rembrandt. It is interesting, but after

viewing nearly a 100 Rembrandt's, you actually get to know the artist and his

body of work, and immediately I thought to myself, "No way this is Rembrandt",

and I was right. The information panel confirmed that it is a Rembrandt

knockoff.

One Dutch atrifact in the painting is the Kraamherenmuts, which is a typical hat worn by new fathers such as the gentleman in the center of this painting. There was a tradtion of the father spending the first ten days after the birth with the baby and mother, as they welcomed guests. The mother is laying on her bed in the upper left part of the painting, in the background. Ominously, a man is leaving making hand jesters above the head of the father, the first clue that something is amiss.

A women presumed to be domestic help is pulling out a nice comfortable red chair for the father to sit in. Meanwhile, broken eggs are spilled out the floor, which is unusual for a dutch household in a society that is religious about being orderly and neat. That would be a second clue to something being not right.

Everyone is having a jolly time and some of the women are collecting money from the father for services of some kind, including the women just to the right of the father (to his left), and the women in the left middle stirring the pot. Sausages are hanging from the kitchens chimney, and being gently handled by a female guest. These are all symbolic of sexual problems in the marriage. The women at the foot of the mothers bed, in profile to the viewer, seems to hiding her pregnancy and drinking an alcoholic beverage. Aside from the egg yolk being splattered on the floor, there is a big brass round utensil (which I somehow missed in my photograph) in the front right of the painting. That is a bed warmer, a device not needed when a couple is sharing a bed. So all these hints tell us that the marriage is quite broken and the pedigree of the child in question. The man walking out the door is likely a self-portrait of Jan Steen himself. He often paints himself or his wife into paintings.

This leads me to a discussion of my second favorite painting at the Wallace

Collection, another Jan Steen work, which, IMO, should probably be returned to

Holland because the Dutch would love this painting and would consider it a

national treasure if it was close to home. The painting is titled "Merrymaking in a Tavern". No painting I had

experienced had made me feel like I was right there, at a specific time and

place, witnessing along with the artist, a grand event, in this case, of the

grand event of every day life.

The music swings through out this painting, and the young girl is seriously excited to be getting into step while the fellow is being swept into the joy of the music. Chatter is happening all around them. This is a prosperous, confident working class, happy with today and looking forward to tomorrow.

It might be perhaps some kind of spring festival as fresh tree branches are hanging joyfully from the rafters of the ceiling. Everyone is at peace, children, dogs, and cats, with families about the tables, 3 generations, and bagpipes being blown. We think of Bagpipes as Scottish, and yet here they are blaring in a Dutch scene, far from their Gaelic heritage.

Unlike most of Jan Steen's painting, this one uses a dramatic perspective wrapped in an exciting architecture. Architecture of Jan Steen is much like a stage set for the theater. It is there to facilitate the acting of the players. In this case though, Jan Steen is using the architecture as a source of enjoyment within the painting. Perhaps, for Steen, this painting is as much about the place as it is the people, although people are always front and center of his paintings. But unlike other works from Jan Steen, this is not a scene where drunkardness is being displayed as a warning to how it can disturb the order of life. Instead, this is a celebration of life, and you are asked to sit and have a beer, and enjoy the crowd. It is not a utopia, as a couple is squabbling on the far left, but everything is manageable, and you feel as though this is real life.

Another aspect of this work that I don't see really discussed is that the painting is cited as being done in the year 1674, which is significant. In 1672, the Netherlands was brutally attacked by the French, English and some German Duchy's which caused a complete collapse of Dutch civilization. Thousands died and the result was that the Republic was pushed aside, and the Monarchy of the House of Orange was given rule. Major naval battles were fought and eventually won through the naval genius of Michiel de Ruyter who defeated the British Navy. The Dutch Crown, William the III of Orange, took over national leadership and built an effective army. Dikes were opened and flooded the countryside creating an effective barrier to ground troops. The French and German troops were stalled on the far side of the water line. The De Witt Brothers, who fought against the house of Orange and ran the Republic were lynched and mutilated in public. Panic broke out. It was a blood bath and the year 1672 is known in the Netherlands as the year of disaster. Despite ultimate victory, the Dutch never again lead the European powers, and a slow and steady decline proceeded from there. It also paved the way for the house of Orange to take over the British Throne, toppling its Catholic Monarchy with the help of English interests within the country. As this history relates to this painting, it seems that the Dutch art market was open to the peaceful, warm and upbeat story that Jan Steen put forward in this work. It is slightly different from previous works, a bit less preachy and a lot more on the happiness, which is perhaps what the public wanted to hear after such a brutal turn of recent events.

This is Netscher's masterpiece - The Lace Maker. It is one of the many great

paintings at the Wallace that doesn't get nearly enough attention, by an

artist, Caspar Netscher, who if he was working in any other period other than

the time period when Hals, Rembrandt and Vemeer were working, would be known

around the world as one of the great artists in history. This painting was actually brought as a

speculative business investment and never successfully resold. Even at that

time, it was not adequately appreciated for the delicate portrait of domestic

life that it is. Consider it a fault of the 19th century. No drama is here.

Just the beauty of a women living her life and applying a craft.

Rembrandt's Titus at the Wallace is a touching image of the Artists son as a boy. There is another, very similar painting of Titus Titus as a young adult from the Dulwich Picture Gallery and comparing them can be interesting. It is one of the few examples of a subject by Rembrandt that captures the same individual as they grew. The only other example of this that I could think of off the cuff is the series of Rembrandt self-portraits. It is interesting to compare the two works, and it is possible that Rembrandt made them similarly as one might take photographs of there children, school pictures.

It is worth explaining some of the background of this painting and the biography of Rembrandt. There is a string of tragedy that runs through Rembrandts life, although, perhaps compared to many individuals who lived through this period, it might be said that tragedy was commonplace. Food security, even in a powerful and wealthy city like Amsterdam, was far from certain. The threat of war and disease was constant, and it was within living memory of the people of this time period, that they recalled the cruelty of the Duke of Alva and the Dutch revolution from the Spanish crown. We are quick today to condemn the colonialism, slavery, and repression of non-European peoples through out the world, but the truth is, that civilization all over the world, during this period, hung by a thread. The French Revolution, coming in a few short years, would be proof of this. No one reading this article would vote against the economic development of Dutch Colonialism when the choice is to face brutality, starvation and subjugation. The Dutch, while famously tolerant at home, were brutal rulers overseas. They were some of the cruellest overlords in Europe. The republican government that represented a population that emerged from death and destruction, to a civilized society is short time, maybe 20 years, was acutely aware of the frailty of its position. They were going to protect there way of life, and their economic interests, their trade advantages, both within the republic and outside, no matter what. Amsterdam, and its fathers, knew that its strength and survival depended on its rule of law, and its commerce. And nothing was going to get in their way.

When you read the biography of artists, and even the life stories of the Amsterdam elite which as a group, were the most powerful men in the world, it is amazing how many of there stories end in tragedy, economic ruin, and dependent on alms. Death and poverty was a constant stalker, a theme in endless numbers of Dutch paintings, even in the high society of Amsterdam. This was more than just religious vigor, but also hard earned experience.

And so it was with Rembrandt. His talent and arrogance lead him to stunning riches as a young man. He married a prized bride in the form of Saskia van Uylenburgh, the first cousin, Hendrick van Uylenburgh, who was his employer and mentor. Saskia was herself a fortunate orphan whose extended family absorbed her and raised her to be a confident and wealthy society women. She had resources, despite the fact that her father and mother both died before she was 12 years old. She was the perfect society girl for the raw and brash talent of Rembrandt.

Saskia and Rembrandt married and they had 4 children, three of which died

not long after birth. The fourth child, the Son Titus who is subject of

this painting, lived, but his mother died about a year after his birth, leaving

Rembrandt with a single living heir, and no wife. It was quite a tragedy,

especially in light of the fact that Rembrandt and Saskia were very much in

love with each other and a power couple. The loss of his wife, who died of

Tuberculosis at the age of 29, was an emotional blow to the artist, and it took

him time to recover.

Through this all, Titus and Rembrandt seemed to have deveoped a very close relationsip. In fact, Rembrandt, for much of his later years, was legally an employee of Titus. This was done to prevent creditors from taking all the works that Rembrandt produced, and to secure his income. Titus becomes the subject of numerous works of Art by Rembrandt. He is most commonly wearing a loose cap, and he has uniformally long locks with a shade of red in his hair color. Titus died in 1668, likely a victem of the Plague, at the age of 26. He had a daughter that survived him. Rembrandt himself died a few months later in October 1669.

The Wallace Collections Titus portait echos back to Rembrands early self-protrait, although the paint is thicker and more impasto. In photography, it is hard to get an exact feel for the color of the painting because the angle or the light and reflection through the varnsh can cause it to apear quite differently depending on where you are viewing it. You can see Rembrandt dig the pointed end of his brush to give an illusion of hair, with splashes of highlight colors, red, brown and white.

Here you can see how hard it is to get the color balance of the photographs collection. There are splashes of moding colors of green and blue tones in the cheeks and the face, that are typical of a Rembrandt protrait. Yet in the second image, they are almost washed out. In addition to that, the age of the varnish causes the texture of the background to darken and flatten. In editing these images, I sometimes try to lighten them up and resurect visual information that is washed out over time. Often my photos are better than what you might observe with the naked eye because of the superior lens I use for close up photography, and color balance. But the process is somewhat speculative, and the conditions for viewing at the Wallace collection is far from ideal.

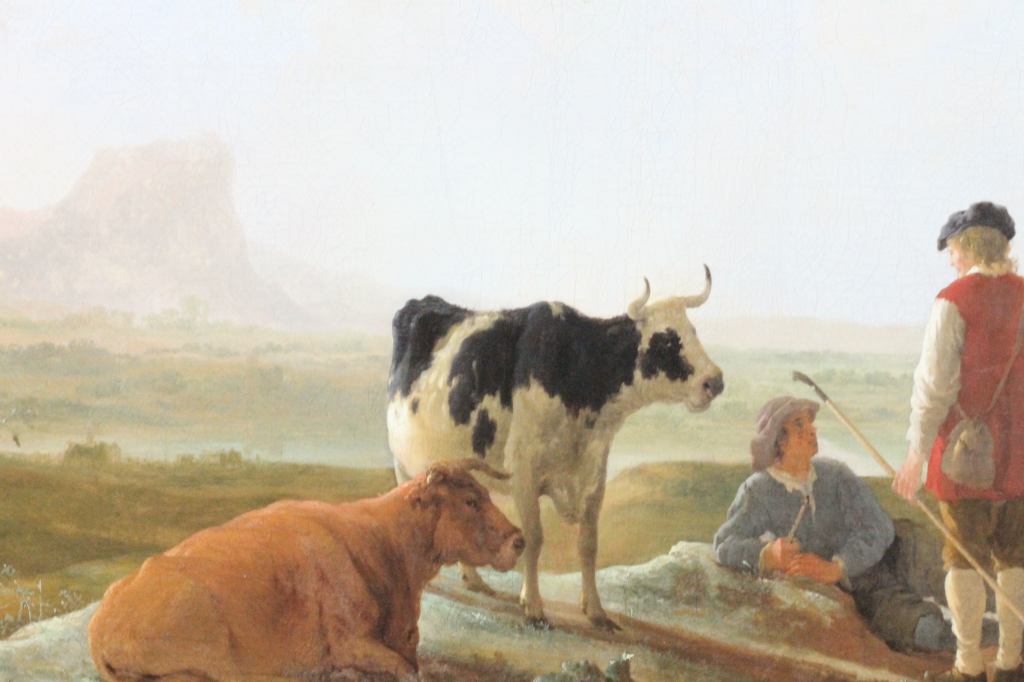

The above painting was done by Salomon Rombouts, an accomplished artist from Harlem in a Flemish style. This was common in Harlem as a lot of refugees from the Southern Netherlands (Belgium) who still were under the ruthless control of the Spanish crown, had crossed the border into Harlem. Many of these were artists who adapted to the new surroundings in the United Republic, and in Harlem, including the Hal's family. Romouts came from a family of artists, as his father also painted, and perhaps other relatives. Little is known about him, but we know that at the time, Landscape painting in Haarlem was very prominant and the most aclaimed landscape painter of the time, Jacob Ruishaal, who also came from a family of painters, had students, and a studio school. So landscape painting in Haarlem was in vogue, and more a few artists engaged in this form of art, one that, if not invented by the Dutch, certainly perfected. Frank Cundall wrote in 1891:

Through the whole of the eighteenth century and through the earlier half of this no landscapes were produced in the Netherlands which could in any way be compared to the work of Ruisdael and Hobbema nor even to that of the Boths Saftleven Wijnants Pijnacker Dekker Van der Hagen Du Bois Rombouts Verboom or Hackaert But within the present generation a school of artists has arisen in Holland which will in future ages be held to have worthily revived the successes of the seventeenth centurySo clearly there was an active school at this time of landscape painters, and many of them in Haarlem. The Wallace Collection has its fair share, with representation of Ruisdaal, Hobbema, and many other worthwhile artists, including this example from Rombouts.

There is a consensus amoung landscape painting experts that there is a pecking order with regard to these artists, with Jacob Ruisdael considered the very best, followed by Hobbema and then others. In fact, Ive read in a few places that Hobbema's work is even somewhat mundane, but I disagree strongly. Hobbema was the king of the landscape and this painting here by the Master Rombouts shows just how unique and strong Hobbema's work is.

As great as this painting is, when you compare it with the 4 or 5 Hobbema compositions above, it is easy to pick out the Hobbema paitings. Rombouts here has painted a number of groves of trees, but they don't formulate a coherent whole. It would be impossible for the trees to be swept this way and that by a real wind. In Hobbema, the entire image is unified by the atmosphere. Colthes, hair, tree leaves, and grass all sway together rythmically. Even the way water falls over rocks and wheels is coherent with the overall painting. Rombout looks somewhat like cut outs, pasted to a sheet, where each cutout lives in its own atmophere obvious to other cut outs about them. And in fact, that is what we observe. You have a tree from a study put here, and a tree from a study placed there, but it is very hard to shape and alter all those sketches into a flowing and coherent scene. That is the greatness of Hobemma.

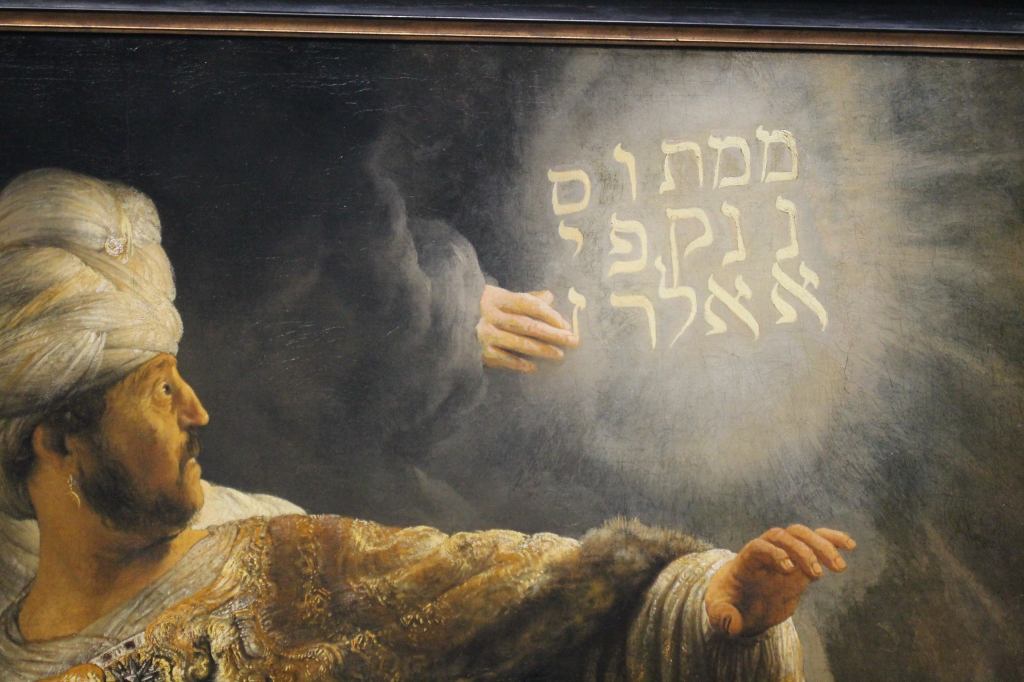

Dietrich - The Circumcision some time after 1720, is one of the few works here that was painted after 1700 and it is one of the most authentic renditions of Jewish Ritual that I've seen in the arts. The painting needs a considerable cleaning so I have tried to fix the color on some of the images.

The Dulwich Picture Gallery is unique in that it is in a residential section of town, near a lovely park. It is one of the oldest publicly available art galleries in the world, built in 1811 by Sir Francois Bourgeois. The collection, by the standards of other great collections, is perhaps a little thin. But the eclectic collection of 17th and 18th century masterpieces, largely Dutch, reflects the effort of individual collectors, but it is still substantial and very enjoyable. A lot of thought was given to constructing a building that allowed light through in order to show the painting. The building is a work of art in of itself and quite amazing to work through. Light shines through the roof into the galleries, lighting up the walls. It is a great day to spend in London, and I highly recommend a visit.

Titus - By Rembrandt

Titus - By Rembrandt

Titus - By Rembrandt

Titus - By Rembrandt

This is a movie of the crazy cab ride out of Dulwich. Cabbies in London earn there money.